.jpg)

Inscribed and signed reproduction of Fountain, 6 5/8 x 8 3/8 inches

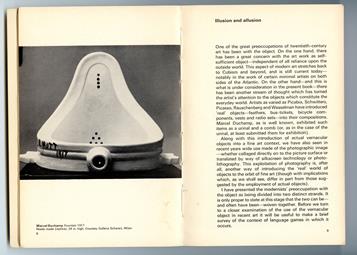

Today, there is little question that Duchamp’s readymade urinal—signed R. Mutt and presented to a jury-free exhibition in New York in 1917 (Fig. 1)—is the single most provocative and influential work of art created by any artist in modern times. It was voted as such by a group of English art professionals in 2004 and, two years later, another group of English art students were surveyed and nominated Duchamp “the most influential artist in the UK.” We can be fairly certain that if a similar survey were conducted among people involved in the world of contemporary art anywhere in the world today, the results would be the same. Duchamp himself shared this opinion. A few years before his death, he told an interviewer: “I’m not at all sure that the concept of the readymade isn’t the most important single idea to come out of my work.”

Fig. 1 Alfred Stieglitz, Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, 1917

In terms of art history, a strong argument could be made that Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913), or Bottlerack (1914), were more important readymades, since they predated the urinal by some three to four years. But those works could be seen only in privacy of Duchamp’s studio, where they were largely ignored. The urinal could not be easily overlooked, for its utilitarian function—to be urinated in by men—could not be easily dismissed or forgotten, particularly when the object was placed on display within the context of a modern art exhibition. Many considered the work to be indecent and, in order to find an excuse for not showing it, an impromptu hanging committee of the exhibition declared the work “by no definition, a work of art.”

Of course, that is the very issue Duchamp’s readymades were intended to evoke, thus forcing the public to ask an even larger question: “Exactly what is it that constitutes a work of art?” It is this question that remains fundamental to an understanding of Duchamp’s original gesture. Indeed, it could be argued that the question is the ultimate essence of the readymade, so much so that it transcends its physical attributes as a work of art. Duchamp was well aware of the important contribution his readymades had made to the history of art, which is one among many factors that led to his decision to reproduce them in an edition through the Galleria Schwarz in Milan in 1964. Thirteen of his most important readymades were replicated in an edition of eight signed and numbered copies, including Fountain (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Fountain, 1917/64, Schwarz edition

It was a reproduction of this work from the edition—one that appeared in a book on Pop Art (Fig. 3)—that Duchamp inscribed at the request of a friend named Maurice, likely the French cartoonist, Maurice Henry (1907-1984). He inscribed it: “Pour Maurice / Cordialement / Marcel Duchamp.” In the last decade of his life, Duchamp signed many reproductions of his work at the request of friends, in order, as the artist Richard Hamilton once explained, “to devalue his work.” But this particular case is different, for it appears that the urinal must have had a special meaning for Henry, who possessed a fairly sophisticated understanding of Fig. 3 Christopher Finch, Pop Art: Object and Image (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1968), cover and pp. 9-10 spread. Duchamp’s work.

Fig. 3 Christopher Finch, Pop Art: Object and Image (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1968) cover and pp. 9-10

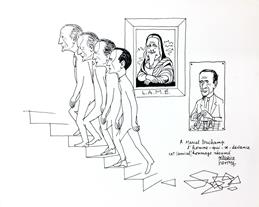

Henry joined the Surrealist group in 1933 and showed in their various International exhibitions. In 1965, he made a cartoon image of Duchamp climbing a staircase, the artist gradually aging as he ascends (Fig. 4). Behind him hang two pictures: on the right an image of Duchamp playing chess and sporting a youthful mustache and goatee, on the left showing the Mona Lisa with a long white beard and mustache, another allusion to aging, but in this case, the aging of Duchamp’s famous alteration of the Mona Lisa with the ribald five-letter inscription L.H.O.O.Q.. The letters below the painting in the Henry cartoon, however, read L.A.M.É, a phonetic transcription of the French phrase “elle a aimé” (she loved), meaning, presumably, that the Mona Lisa herself approved of Duchamp’s alteration. The inscription above Henry’s signature reads “À Marcel Duchamp / l’homme – qui – se – deviance / cet (amical) hommage résumé [To Marcel Duchamp / the man – who – is ahead – of – himself].

Fig. 4. Maurice Henry, Marcel Duchamp, cartoon, ca. 1965. Philadelphia Museum of Art